It’s October 2023, the term has started and I am asked to fill in an ethics form, but I haven’t really got my head around what an action research project really is, and how to go about coming up with an idea, let alone plan for it.

In her booklet “Action research for professional development” Jean McNiff (2002) describes Action Research as

Action research is a term which refers to a practical way of looking at your own work to check that it is as you would like it to be.

Jean McNiff (2002)

A self-reflective practice into my own behaviour and the reasons for it. Rather than testing a fixed hypothesis, an action research project starts with an idea, trying it out, seeing how it goes and reflecting on in. Generally, it starts with the question ‘How do I improve my work?’

In my other work, besides teaching, I am about to finish my PhD research on wearable sleep-tracking technology. I’m particularly interested in the factors impacting sleep that are beyond an individual’s control such as social, environmental or economic factors that can’t be captured by a sleep-tracker. The public discourse on sleep emphasises both the benefits of sleep for physical and mental health, well-being and functioning and the risks associated with poor sleep quality and quantity. This discourse is also associated with an assumed widespread sleep deprivation and new, increasingly diagnosed sleep disorders. De Christofaro and Chiodo (2023) and others refer to this concurrence of emergent concerns as ‘the sleep crisis’. Studies show that in the past half-century, the self-reported sleep quality and duration among adults have decreased (Ford et al., 2015; Kronholm et al., 2008). Among factors contributing to sub-optimal sleep duration, researchers have identified lower socioeconomic status (Stamatakis et al., 2007), lifestyle and stress (Bixler, 2009; Seixas et al., 2015; Vgontzas et al., 2008).

Both from research and personal experience I am aware of how too little or bad sleep impacts cognitive functioning and thus, I assume, the learning experience of students. I would like to find out more about the relationship between sleepiness and the student’s experience in the classroom. I’m inspired by the activist Tricia Hersey, founder of The Nap Ministry and author of the bestselling book Rest is Resistance (2022). Writing and speaking from the position of a Black woman she articulates the sleep crisis as a public health, racial and social justice issue and poses the vision of rest as a radical way to collectively push back and disrupt.

Newly propagated ideas about the importance of rest is not a trend. “It is the ancient work of liberation. To frame rest as something Black people are finally reclaiming is to erase the history of so many of my [Tricia Hersey’s] ancestors and those living today, who have consistently seen rest as an important part of living in resistance: Audre Lorde, Alice Walker, Harriet Tubman […] There is nothing new about Black death, anti-blackness and oppression.” The experience of Black bodies being pushed to their limits, treated like machines during the transatlantic slave-trade, is closely tied to the advent of capitalism and our current system of labour. To rest was to resist.

To face the traumatic colonial history, questioning why we still participate in a system treating human bodies as non-human machines built on white supremacy and exploitation, is a suitable frame for thinking about education and academia, which in many ways mimic the neoliberal economy. By understanding how sleepiness affects the student’s ability to learn I hope to find ways to incorporate rest and its ability to hold space for communal dreaming, care and healing of tired bodies into my teaching.

I submitted a first draft of the ethics form for our tutorial on October 11 with an initial research question: “How does the level of sleepiness of both myself and students affect participation in a seminar?” The feedback I got, both from my tutor and peers, was very helpful, particularly the remark that linking a study to participation, an assessment criteria, was an ethical issue that needed to be reworked. I also really appreciated feedback from the tutorial group to hold a lecture in my pyjamas, or bring a bed to classroom, but while these ideas seemed very exciting to me they also made me feel overwhelmed by it all and, in fact, tired as I was already exhausted by having just started a new job in a different country, finishing my PhD and working on two other projects. After pondering a bit more on what to do for this project I decided to give up and postpone the ARP to the next year.

***

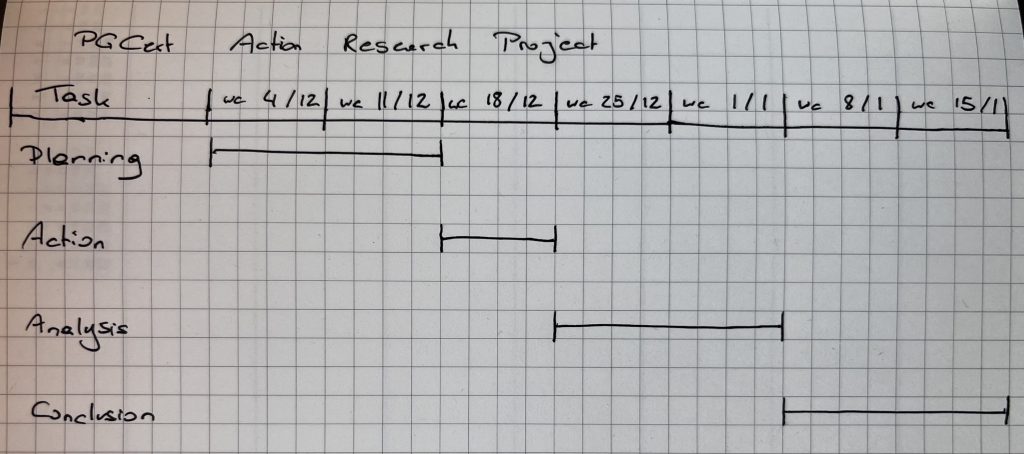

Fast forward to 30 November 2023. I’m co-teaching a class at LCC and we have a guest from the PGCert in our workshop. She is conducting her study for her Action Research Project and so is my co-teacher. Their research inspires me to pick up my loose ends and find a way to complete the PGCert. I have about 7 weeks left and the PGCert tutor team encourages me to go ahead with my study. I device a plan to conduct the study on time.

I move away from linking the study to participation in a seminar I rephrase my research question.

“As an educator and student myself I am aware that stress and exhaustion are present at different levels of intensity during different times of the year. This can be either through academic deadlines but also personal circumstances and has effects on the learning experience and engagement. I am interested to gather the students’ perspective on how sleepiness (I refer here to sleepiness, as stress is one of the key contributing factors for bad sleep quality and it is subjectively measurable with standardised scales) has an effect on their experience in the classroom. I want to use the insights from this study to plan for future modules and challenge academic norms that might be conducive to stress. How does the level of sleepiness in students affect their learning experience?”

As I am mostly teaching at the University of Applied Arts Vienna this term I agreed with the team for quality assurance of teaching that I can gather data for this study during my seminar.

To gather data about the levels of sleepiness and how they affect learning experience I developed a study in two stages. First, the students who agree to participate will answer questions via a Microsoft form, including self-assessing their momentary level of sleepiness with the Stanford Sleepiness Scale (SSS) and their general level of daytime sleepiness using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) (Shahid et.al., 2010), as well as other questions about sleepiness in relation to different times throughout the semester and what factors contribute to their sleepiness.

Then the students will be asked to collaboratively write fictional anecdotes following different prompts in the format of an Exquisit Corpse on sheets of paper. The prompts will be given starting from different levels of sleepiness from the SSS of a fictional student participating in the particular seminar. Fictional anecdotes collectively written as an Exquisit Corpse seems a suitable format for data collection, as it respects student’s anonymity and might overcome the limitation that students can talk in the voice of an imagined character rather than from their own experience, which they might feel uncomfortable sharing. In addition to that, the exquisite corpse, a surrealist parlour game, alludes to the ‘collective dreaming’ I would like to further investigate as a method for teaching after this study. More details can be found in the ethics form.

Given the timeline and my seminar-dates I schedule the study for my session on Tuesday, 19 December 2023. I already informed the students in the previous seminar and reminded them about the study in an email one week before the study.

References

Edward Bixler. 2009. Sleep and Society: An Epidemiological Perspective. Sleep Medicine 10 (Sept. 2009), 3–6.

De Christofaro, D. and Chiodo, S. (2023). Quantified Sleep: Self-Tracking Technologies and the Reshaping of 21st-Century Subjectivity. Historical Social Research Vol. 48 , No. 2 (2023)

Ford, E. S., Cunningham, T. J., and Croft, J. B. (2015). Trends in Self-Reported Sleep Duration among US Adults from 1985 to 2012. Sleep 38, 829–832

Tricia Hersey. 2022. Rest is Resistance: Free Yourself from Grind Culture and Reclaim Your Life. London: Aster.

Kronholm, E., Partonen, T., Laatikainen, T., Peltonen, M., H ̈arm ̈a, M., Hublin, C., et al. (2008). Trends in Self-Reported Sleep Duration and Insomnia-Related Symptoms in Finland from 1972 to 2005: A Comparative Review and Re-Analysis of Finnish Population Samples. Journal of Sleep Research 17, 54–62.

Jean McNiff. 2002. Action research for professional development: Concise advice for new action researchers. 3rd Edition, 2002.

Azizi Seixas, Joao Nunes, Collins Airhihenbuwa, Natasha Williams, Caryl James, Girardin Jean-Louis, and S. R Pandi-Perumal. 2015. Linking Emotional Distress to Unhealthy Sleep Duration: Analysis of the 2009 National Health Interview Survey. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment (Sept. 2015), 2425.

Azmedh Shahid, Jianhua Shen, and Colin M. Shapiro. 2010. Measurements of sleepiness and fatigue. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 69 (2010) 81-89.

Katherine A. Stamatakis, George A. Kaplan, and Robert E. Roberts. 2007. Short Sleep Duration Across Income, Education, and Race/Ethnic Groups: Population Prevalence and Growing Disparities During 34 Years of Follow-Up. Annals of Epidemiology 17, 12 (Dec. 2007), 948–955.

A N Vgontzas, H-M Lin, M Papaliaga, S Calhoun, A Vela-Bueno, G P Chrousos, and E O Bixler. 2008. Short Sleep Duration and Obesity: The Role of Emotional Stress and Sleep Disturbances. International Journal of Obesity 32, 5 (May 2008), 801–809.